People Connect With Family History in Black Cemetery by Matt Allibone

| Cecilia Beaux | |

|---|---|

Cecilia Beaux c. 1888 | |

| Built-in | Eliza Cecilia Beaux (1855-05-01)May one, 1855 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Died | September 17, 1942(1942-09-17) (aged 87) Gloucester, Massachusetts |

| Nationality | American |

| Didactics | Francis Adolf Van der Wielen, Académie Julian, Académie Colarossi |

| Known for | Portrait painting |

| Movement | Impressionism |

| Awards | Mary Smith Prize, PAFA (1885, 1887, 1891, 1892) Starting time Prize, Carnegie Establish (1899) Temple Gold Medal, PAFA (1900) Gold Medal, Exposition Universelle (1900) |

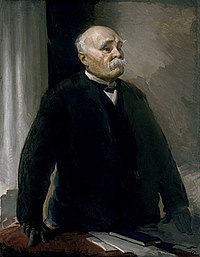

Cecilia Beaux (May ane, 1855 – September 17, 1942) was an American order portraitist, whose subjects included Outset Lady Edith Roosevelt, Admiral Sir David Beatty and Georges Clemenceau.

Trained in Philadelphia, she went on to study in Paris, strongly influenced by ii classical painters Tony Robert-Fleury and William-Adolphe Bouguereau, who avoided advanced movements. In turn, she resisted impressionism and cubism, remaining a strongly private figurative artist. Her style, however, invited comparisons with John Singer Sargent; at one exhibition, Bernard Berenson joked that her paintings were the best Sargents in the room. She could flatter her subjects without artifice, and showed great insight into graphic symbol. Like her instructor William Sartain, she believed there was a connection between physical characteristics and behavioral traits.

Beaux became the first woman teacher at the Pennsylvania University of the Fine Arts. She was awarded a golden medal for lifetime achievement past the National Institute of Arts and Messages, and honoured by Eleanor Roosevelt equally "the American woman who had made the greatest contribution to the civilization of the world".

Biography [edit]

Early life [edit]

Eliza Cecilia Beaux was born on May one, 1855 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[one] She was the youngest girl of French silk manufacturer Jean Adolphe Beaux and teacher Cecilia Kent Leavitt. Her mother was the girl of prominent businessman John Wheeler Leavitt of New York City and his married woman Cecilia Kent of Suffield, Connecticut.[2] Cecilia Kent Leavitt died from puerperal fever 12 days subsequently giving nativity at age 33.[3] Cecilia "Leilie" Beaux and her sis Etta were subsequently raised by their maternal grandmother and aunts, primarily in Philadelphia.[four] [5] Her father, unable to bear the grief of his loss, and feeling adrift in a strange country, returned to his native France for xvi years, with only one visit back to Philadelphia.[six] He returned when Cecilia was 2, but left four years after after his business failed. As she confessed later, "We didn't dearest Papa very much, he was so foreign. We thought him peculiar." Her father did have a natural aptitude for drawing and the sisters were charmed by his whimsical sketches of animals. After, Beaux would detect that her French heritage would serve her well during her pilgrimage and training in French republic.[seven]

In Philadelphia, Beaux's aunt Emily married mining engineer William Foster Biddle, whom Beaux would afterward describe as "after my grandmother, the strongest and well-nigh beneficent influence in my life." For fifty years, he cared for his nieces-in-law with consistent attention and occasional financial support.[eight] Her grandmother, on the other hand, provided day-to-day supervision and kindly subject field. Whether with housework, handiwork, or academics, Grandma Leavitt offered a pragmatic framework, stressing that "everything undertaken must exist completed, conquered." The Civil State of war years were especially challenging, merely the extended family survived despite little emotional or financial support from Beaux's father.[9]

After the state of war, Beaux began to spend some fourth dimension in the household of "Willie" and Emily, both skillful musicians. Beaux learned to play the pianoforte only preferred singing. The musical atmosphere afterward proved an reward for her artistic ambitions. Beaux recalled, "They understood perfectly the spirit and necessities of an creative person's life."[10] In her early teens, she had her outset major exposure to art during visits with Willie to the nearby Pennsylvania University of the Fine Arts, one of America's foremost art schools and museums. Though fascinated by the narrative elements of some of the pictures, particularly the Biblical themes of the massive paintings of Benjamin West, at this point Beaux had no aspirations of condign an artist.[11]

Her childhood was a sheltered though more often than not happy one. As a teen she already manifested the traits, every bit she described, of "both a realist and a perfectionist, pursued by an uncompromising passion for carrying through."[12] She attended the Misses Lyman School and was merely an average pupil, though she did well in French and Natural History. However, she was unable to beget the extra fee for art lessons.[13] At age 16, Beaux began art lessons with a relative, Catherine Ann Drinker, an accomplished artist who had her ain studio and a growing clientele. Drinker became Beaux's part model, and she continued lessons with Drinker for a yr. She then studied for two years with the painter Francis Adolf Van der Wielen, who offered lessons in perspective and drawing from casts during the fourth dimension that the new Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts was under construction. Given the bias of the Victorian age, female students were denied direct study in beefcake and could not attend drawing classes with live models (who were often prostitutes) until a decade subsequently.[14]

At 18, Beaux was appointed equally a drawing teacher at Miss Sanford'southward School, taking over Drinker's post. She also gave private fine art lessons and produced decorative art and small portraits. Her own studies were generally self-directed. Beaux received her first introduction to lithography doing copy work for Philadelphia printer Thomas Sinclair and she published her offset piece of work in St. Nicholas mag in December 1873.[fifteen] Beaux demonstrated accuracy and patience as a scientific illustrator, creating drawings of fossils for Edward Drinker Cope, for a multi-volume report sponsored by the U.S. Geological Survey. However, she did non find technical illustration suitable for a career (the extreme exactitude required gave her pains in the "solar plexus"). At this stage, she did not withal consider herself an artist.[16] [17]

Beaux began attending the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in 1876, then nether the dynamic influence of Thomas Eakins, whose cracking work The Gross Clinic had "horrified Philadelphia Exhibition-goers as a gory spectacle" at the Centennial Exhibition of 1876.[18] She steered clear of the controversial Eakins, though she much admired his work. His progressive teaching philosophy, focused on anatomy and live study (and allowed the female students to partake in segregated studios), eventually led to his firing as director of the Academy. She did non marry herself with Eakins' agog educatee supporters, and afterward wrote, "A curious instinct of cocky-preservation kept me outside the magic circle."[19] Instead, she attended costume and portrait painting classes for three years taught by the ailing managing director Christian Schussele.[20] Beaux won the Mary Smith Prize at the Pennsylvania University of the Fine Arts exhibitions in 1885, 1887, 1891, and 1892.[21]

After leaving the University, the 24-year-old Beaux decided to try her hand at porcelain painting and she enrolled in a course at the National Art Training School. She was well suited to the precise work but later wrote, "this was the lowest depth I ever reached in commercial fine art, and although it was a period when youth and romance were in their offset attendance on me, I call up information technology with gloom and record it with shame."[22] She studied privately with William Sartain, a friend of Eakins and a New York artist invited to Philadelphia to teach a grouping of art students, starting in 1881. Though Beaux admired Eakins more and thought his painting skill superior to Sartain's, she preferred the latter's gentle didactics way which promoted no particular artful arroyo.[23] Different Eakins, nonetheless, Sartain believed in phrenology and Beaux adopted a lifelong belief that concrete characteristics correlated with behaviors and traits.[23]

Beaux attended Sartain'southward classes for 2 years, then rented her own studio and shared information technology with a group of women artists who hired a live model and continued without an instructor. After the group disbanded, Beaux set in hostage to prove her artistic abilities. She painted a large canvas in 1884, Les Derniers Jours d'Enfance, a portrait of her sis and nephew whose composition and style revealed a debt to James McNeill Whistler and whose field of study thing was akin to Mary Cassatt'south mother-and-child paintings.[24] It was awarded a prize for the best painting by a female artist at the University, and further exhibited in Philadelphia and New York. Following that seminal painting, she painted over l portraits in the side by side three years with the zeal of a committed professional person artist. Her invitation to serve as a juror on the hanging committee of the Academy confirmed her acceptance amidst her peers.[25] In the mid-1880s, she was receiving commissions from notable Philadelphians and earning $500 per portrait, comparable to what Eakins commanded.[26] When her friend Margaret Bush-Dark-brown insisted that Les Derniers was skillful enough to be exhibited at the famed Paris Salon, Beaux relented and sent the painting abroad in the intendance of her friend, who managed to get the painting into the exhibition.[26]

Paris [edit]

At 32, despite her clear success in Philadelphia, Beaux decided that she nonetheless needed to accelerate her skills. She left for Paris with cousin May Whitlock, forsaking several suitors and overcoming the objections of her family. There she trained at the Académie Julian,[27] the largest fine art school in Paris, and at the Académie Colarossi, receiving weekly critiques from established masters like Tony Robert-Fleury and William-Adolphe Bouguereau.[28] She wrote, "Fleury is much less benign than Bouguereau and don't temper his severities…he hinted of possibilities earlier me and equally he rose said the nicest thing of all, 'we will do all nosotros can to help you'…I desire these men…to know me and recognize that I can exercise something."[29] Though brash regularly of Beaux'south progress abroad and to "non exist worried about any indiscretions of ours", her Aunt Eliza repeatedly reminded her niece to avoid the temptations of Paris, "Call back you are first of all a Christian – then a woman and last of all an Artist."[30]

Twilight Confidences, 1888

When Beaux arrived in Paris, the Impressionists, a group of artists who had begun their own series of independent exhibitions from the official Salon in 1874, were get-go to lose their solidarity. Also known as the "Independents" or "Intransigents", the grouping which at times included Degas, Monet, Sisley, Caillebotte, Pissarro, Renoir, and Berthe Morisot, had been receiving the wrath of the critics for several years. Their art, though varying in style and technique, was the antonym of the blazon of Academic art in which Beaux was trained and of which her teacher William-Adolphe Bouguereau was a leading main. In the summer of 1888, with classes in summer recess, Beaux worked in the fishing village of Concarneau with the American painters Alexander Harrison and Charles Lazar. She tried applying the plein-air painting techniques used by the Impressionists to her own landscapes and portraiture, with little success.[31] Unlike her predecessor Mary Cassatt, who had arrived virtually the start of the Impressionist movement 15 years before and who had absorbed it, Beaux's artistic temperament, precise and true to observation, would non align with Impressionism and she remained a realist painter for the rest of her career, even equally Cézanne, Matisse, Gauguin, and Picasso were first to take fine art into new directions.[32] Beaux mostly admired classic artists similar Titian and Rembrandt. Her European training did influence her palette, nonetheless, and she adopted more than white and paler coloration in her oil painting, specially in depicting female subjects, an approach favored by Sargent as well.[33]

Dorothea and Francesca -1898

Return to Philadelphia [edit]

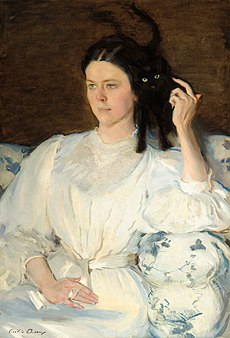

Sita and Sarita (Jeune Fille au Conversation). Portrait of Sarah Allibone Leavitt, 1893–1894. Collection of the Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Back in America in 1889, Beaux proceeded to paint portraits in the 1000 manner, taking as her subjects members of her sis's family too every bit the elite of Philadelphia. In making her decision to devote herself to fine art, she also thought it was best not to marry, and in choosing male person company she selected men who would not threaten to sidetrack her career.[34] She resumed life with her family, and they supported her fully, acknowledging her chosen path and demanding of her footling in the way of household responsibilities, "I was never in one case asked to exercise an errand in town, some bit of shopping…then well did they empathize."[35] She developed a structured, professional person routine, arriving promptly at her studio, and expected the aforementioned from her models.

The five years that followed were highly productive, resulting in over forty portraits.[36] In 1890 she exhibited at the Paris Exposition, obtained in 1893 the gilt medal of the Philadelphia Fine art Guild, and also the Contrivance prize at the New York National Academy of Design.[37] [38] She exhibited her work at the Palace of Fine Arts and The Woman's Building at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Illinois.[39] Her portrait of The Reverend Matthew Blackburne Grier was specially well-received, as was Sita and Sarita, a portrait of her cousin Charles Due west. Leavitt's wife Sarah (Allibone) Leavitt in white, with a pocket-size blackness true cat perched on her shoulder, both gazing out mysteriously. The mesmerizing effect prompted ane critic to bespeak out "the witch-like weirdness of the black kitten" and for many years, the painting solicited questions by the press. But the result was not pre-planned, as Beaux'south sister afterwards explained, "Delight make no mystery virtually it—it was just an idea to put the black kitten on her cousin'southward shoulder. Nix deeper."[xl] Beaux donated Sita and Sarita to the Musée du Luxembourg,[41] but just afterward making a copy for herself.[42] Some other highly regarded portrait from that period is New England Woman (1895), a well-nigh all-white oil painting which was purchased by the Pennsylvania University of the Fine Arts.

Ernesta by Cecilia Beaux 1894

In 1895 Beaux became the first woman to have a regular teaching position at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where she instructed in portrait drawing and painting for the next xx years.[43] That rare blazon of achievement by a woman prompted ane local newspaper to state, "It is a legitimate source of pride to Philadelphia that one of its almost cherished institutions has made this innovation." She was a popular instructor.[40] In 1896, Beaux returned to French republic to see a group of her paintings presented at the Salon. Influential French critic M. Henri Rochefort commented, "I am compelled to admit, not without some chagrin, that not one of our female artists…is strong enough to compete with the lady who has given usa this yr the portrait of Dr. Grier. Composition, mankind, texture, sound drawing—everything is at that place without affectation, and without seeking for upshot."[44]

Mother and Girl Cecilia Beaux 1898

Mrs. Robert Chapin and Girl Christina by Cecilia Beaux, 1902

Cecilia Beaux considered herself a "New Woman", a 19th-century women who explored educational and career opportunities that had generally been denied to women. In the tardily 19th century Charles Dana Gibson depicted the "New Woman" in his painting, The Reason Dinner was Tardily, which is "a sympathetic portrayal of creative aspiration on the function of young women" as she paints a visiting policeman.[45] [46] This "New Adult female" was successful, highly trained, and ofttimes did not marry; other such women included Ellen Mean solar day Unhurt, Mary Cassatt, Elizabeth Nourse and Elizabeth Coffin.[47]

Beaux was a member of Philadelphia's The Plastic Order.[48] Other members included Elenore Abbott, Jessie Willcox Smith, Violet Oakley, Emily Sartain, and Elizabeth Shippen Greenish. Many of the women who founded the organization had been students of Howard Pyle. It was founded to provide a means to encourage 1 another professionally and create opportunities to sell their works of art.[49] [50]

New York [edit]

By 1900 the need for Beaux's work brought clients from Washington, D.C., to Boston, prompting the artist to movement to New York Metropolis; it was in that location she spent the winters, while summering at Green Alley, the dwelling and studio she had built in Gloucester, Massachusetts.[51] Beaux's friendship with Richard Gilder, editor-in-chief of the literary mag The Century, helped promote her career and he introduced her to the aristocracy of society.[52] Amongst her portraits which followed from that association are those of Georges Clemenceau; Kickoff Lady Edith Roosevelt and her daughter; and Admiral Sir David Beatty. She also sketched President Teddy Roosevelt during her White House visits in 1902, during which "He sat for two hours, talking virtually of the time, reciting Kipling, and reading scraps of Browning."[53] Her portraits Fanny Travis Cochran, Dorothea and Francesca, and Ernesta and her Little Brother, are fine examples of her skill in painting children;[38] Ernesta with Nurse, one of a series of essays in luminous white, was a highly original composition, seemingly without precedent.[54] She became a member of the National Academy of Pattern in 1902.[38] and won the Logan Medal of the arts at the Fine art Constitute of Chicago in 1921.

Greenish Alley [edit]

By 1906, Beaux began to live twelvemonth-round at Green Alley, in a comfortable colony of "cottages" belonging to her wealthy friends and neighbors. All three aunts had died and she needed an emotional pause from Philadelphia and New York. She managed to detect new subjects for portraiture, working in the mornings and enjoying a leisurely life the rest of the time. She carefully regulated her energy and her activities to maintain a productive output, and considered that a key to her success. On why and so few women succeeded in art as she did, she stated, "Strength is the stumbling cake. They (women) are sometimes unable to stand the difficult work of it twenty-four hours in and twenty-four hours out. They go tired and cannot reenergize themselves."[55]

While Beaux stuck to her portraits of the aristocracy, American fine art was advancing into urban and social subject matter, led by artists such as Robert Henri who espoused a totally different aesthetic, "Work with neat speed..Accept your energies alert, upwardly and active. Do information technology all in one sitting if you can. In i minute if you tin. There is no use delaying…Stop studying water pitchers and bananas and paint everyday life." He advised his students, amongst them Edward Hopper and Rockwell Kent, to live with the common homo and pigment the common homo, in full opposition to Cecilia Beaux's artistic methods and subjects.[56] The clash of Henri and William Merritt Chase (representing Beaux and the traditional art institution) resulted in 1907 in the contained exhibition past the urban realists known as "The Eight" or the Ashcan School. Beaux and her art friends dedicated the former order, and many thought (and hoped) the new movement to be a passing fad, simply it turned out to exist a revolutionary turn in American art.

Portrait of Mrs. Albert J. Beveridge, 1916

In 1910, her honey Uncle Willie died. Though devastated by the loss, at fifty-five years of historic period, Beaux remained highly productive. In the next 5 years she painted almost 25 percentage of her lifetime output and received a steady stream of honors.[57] She had a major exhibition of 35 paintings at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., in 1912. Despite her continuing production and accolades, however, Beaux was working against the current of tastes and trends in art. The famed "Arsenal Show" of 1913 in New York City was a landmark presentation of ane,200 paintings showcasing Modernism. Beaux believed that the public, initially of mixed stance about the "new" art, would ultimately turn down it and return its favor to the Pre-Impressionists.

Beaux was crippled after breaking her hip while walking in Paris in 1924. With her health impaired, her work output dwindled for the remainder of her life.[33] That aforementioned year Beaux was asked to produce a cocky-portrait for the Medici collection in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence.[58] In 1930 she published an autobiography, Background with Figures.[33] Her later life was filled with honors. In 1930 she was elected a fellow member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters; in 1933 came membership in the American University of Arts and Letters, which ii years later organized the starting time major retrospective of her work. Also in 1933 Eleanor Roosevelt honored Beaux as "the American woman who had fabricated the greatest contribution to the culture of the earth".[59] In 1942 The National Establish of Arts and Messages awarded her a gold medal for lifetime accomplishment.

Death and disquisitional regard [edit]

Landscape with Farm Building, 1888

Cecilia Beaux died at the age of 87 on September 17, 1942, in Gloucester, Massachusetts.[1] She was buried at Due west Laurel Hill Cemetery in Bala Cynwyd, Pennsylvania. In her will she left a Duncan Phyfe rosewood secretaire made for her father to her cherished nephew Cecil Kent Drinker, a Harvard physician whom she had painted as a immature boy.[60] [61]

Beaux was included in the 2018 exhibit Women in Paris 1850-1900 at the Clark Fine art Institute.[62]

Though Beaux was an individualist, comparisons to Sargent would prove inevitable, and often favorable. Her strong technique, her perceptive reading of her subjects, and her ability to flatter without falsifying, were traits similar to his.

Homo with the Cat (Henry Sturgis Drinker), 1898

"The critics are very enthusiastic. (Bernard) Berenson, Mrs. Coates tells me, stood in forepart of the portraits – Miss Beaux's iii – and wagged his head. 'Ah, yes, I see!' Some Sargents. The ordinary ones are signed John Sargent, the best are signed Cecilia Beaux, which is, of grade, nonsense in more means than one, only it is role of the generous chorus of praise."[63] Though overshadowed by Mary Cassatt and relatively unknown to museum-goers today, Beaux's craftsmanship and extraordinary output were highly regarded in her fourth dimension. While presenting the Carnegie Constitute's Gilt Medal to Beaux in 1899, William Merritt Chase stated "Miss Beaux is non merely the greatest living woman painter, but the all-time that has ever lived. Miss Beaux has washed away entirely with sex [gender] in art."[64] [65]

During her long productive life equally an artist, she maintained her personal aesthetic and high standards against all distractions and countervailing forces. She constantly struggled for perfection, "A perfect technique in anything," she stated in an interview, "means that at that place has been no break in continuity betwixt the formulation and the act of performance." She summed up her driving piece of work ethic, "I can say this: When I endeavor anything, I take a passionate decision to overcome every obstruction…And I do my own work with a refusal to have defeat that might virtually exist called painful."[66]

References [edit]

- ^ a b Kuiper, Kathleen. "Cecilia Beaux", Encyclopædia Britannica Online, Retrieved May 22, 2015.

- ^ John Austin Stevens; Benjamin Franklin DeCosta; Henry Phelps Johnston; Martha Joanna Lamb; Nathan Gillett Pond; William Abbatt (1890). The Mag of American History with Notes and Queries. A.South. Barnes.

- ^ Tappert, page i.

- ^ Wadsworth Atheneum; Elizabeth Mankin Kornhauser; Elizabeth R. McClintock; Amy Ellis (1996). American Paintings Before 1945 in the Wadsworth Atheneum. Yale University Press. ISBN0-300-06672-4.

- ^ Who's Who in Pennsylvania. 1908.

- ^ Alice A. Carter, Cecilia Beaux, Rizzoli, New York, 2005, p. 11, ISBN 0-8478-2708-9

- ^ Carter, p. 15

- ^ Carter, p. eighteen

- ^ Carter, p. xix

- ^ Carter, p. xx

- ^ Carter, p. 25

- ^ Carter, p. 29

- ^ Carter, p. 31

- ^ Carter, p. 37

- ^ Carter, p. 45

- ^ Beaux, pp. 77-80

- ^ Carter, pp. 48-49

- ^ Carter, p. 54

- ^ Carter, p. 59

- ^ Carter, p. 55

- ^ Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (1914). Catalogue of the Annual Exhibition of Painting and Sculpture. pp. 10–11.

- ^ Carter, p. 63

- ^ a b Carter, p. 65

- ^ Carter, p. 67

- ^ Carter, p. 69

- ^ a b Carter, p. 70

- ^ "nmwa.org".

- ^ Carter, p. 77

- ^ Carter, p. 82

- ^ Carter, p. 84

- ^ Carter, p. 87

- ^ Carter, p. 91

- ^ a b c Roberts, Norma J., ed. (1988), The American Collections , Columbus Museum of Art, p. 44, ISBN0-8109-1811-0 .

- ^ Carter, p. 105

- ^ Carter, p. 106

- ^ Carter, p. 107

- ^ Carter, p. 108

- ^ a b c Chisholm 1911.

- ^ Nichols, K. L. "Women'south Fine art at the Globe'due south Columbian Fair & Exposition, Chicago 1893". Retrieved Baronial 3, 2018.

- ^ a b Carter, p. 114

- ^ Tappert, p. 32

- ^ "Sita and Sarita c. 1921". National Gallery of Art. Retrieved August 19, 2018.

- ^ Goodyear, p. 12

- ^ Carter, p. 120

- ^ Nancy Mowall Mathews. "The Greatest Woman Painter": Cecilia Beaux, Mary Cassatt, and Issues of Female person Fame. Archived March 14, 2015, at the Wayback Motorcar The Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Retrieved March fifteen, 2014.

- ^ The Gibson Daughter as the New Adult female. Library of Congress. Retrieved March 15, 2014.

- ^ Holly Pyne Connor; Newark Museum; Frick Art & Historical Eye. Off the Pedestal: New Women in the Art of Homer, Chase, and Sargent. Rutgers University Printing; 2006. ISBN 978-0-8135-3697-2. p. 25.

- ^ "Plastic Lodge Noted Past Members" Archived Apr 7, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Plastic Order, Retrieved July 28, 2018.

- ^ The Plastic Lodge. The Historical Club of Pennsylvania. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ Jill P. May; Robert Due east. May; Howard Pyle. Howard Pyle: Imagining an American School of Art. University of Illinois Press; 2011. ISBN 978-0-252-03626-ii. p. 89.

- ^ Making of America Projection (1910). The Century. Scribner & Co.

- ^ Carter, p. 123

- ^ Carter, p. 134

- ^ Goodyear, p. 78

- ^ Carter, p. 149

- ^ Carter, p. 153

- ^ Carter, p. 162

- ^ "Self Portrait, Cecilia Beaux, installation at the Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy, Smithsonian Athenaeum of American Art".

- ^ Tappert, p. 5

- ^ Winter Antiques Show Bows in for 51st Yr, R. Scudder Smith, Antiques and the Arts Online Archived February thirteen, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mangravite, Andrew (March 8, 2008). "'Cecilia Beaux' at Pennsylvania Academy". Broad Street Review . Retrieved August xix, 2018.

- ^ Madeline, Laurence (2017). Women artists in Paris, 1850-1900. Yale University Press. ISBN978-0300223934.

- ^ Goodyear, p. 17

- ^ Carter, p. 127

- ^ "Cecilia Beaux's Contemporaries Judged Her to Exist the Cat's Meow; History Sees a Bit of a Chameleon". Washington Post. March 9, 2008. Retrieved Baronial 19, 2018.

- ^ Carter, p. 173

Sources [edit]

- Grafly, Dorothy. "Cecilia Beaux" in Edward T. James, Janet Wilson James, and Paul S. Boyer, eds. Notable American Women, 1607–1950: A Biographical Dictionary (1971)

- Beaux, Cecilia. Background with Figures: Autobiography of Cecilia Beaux. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1930.

- Goodyear, Jr., Frank H., and others., Cecilia Beaux: Portrait of an Artist. Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1974. Library of Congress Catalog No. 74-84248

- Tappert, Tara Leigh, Cecilia Beaux and the Art of Portraiture. Smithsonian Institution, 1995. ISBN i-56098-658-1

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain:Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Beaux, Cecilia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. iii (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 600.

External links [edit]

- Cecilia Beaux from Smithsonian American Art Museum

- A finding aid to the Cecilia Beaux Papers, 1863-1968, in the Archives of American Fine art, Smithsonian Institution

- Portrait of Mrs. John Wheeler Leavitt, 1885, grandmother of Cecilia Beaux, Westmoreland Museum of American Art, Greensburg, Pa., ExplorePAHistory.com

- Aimee Ernesta and Eliza Cecilia: Two Sisters, Two Choices, Tara Leigh Tappert, The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, July 2000, pp. 249–291

- Cecilia Beaux's Contemporaries Judged Her to Exist the True cat's Meow; History Sees a Bit of a Chameleon, The Washington Post, March 9, 2008, washingtonpost.com

- Documenting the Gilt Age: New York City Exhibitions at the Turn of the 20th Century A New York Art Resources Consortium [https://web.annal.org/web/20190410182041/https://gildedage2.omeka.internet/exhibits/testify/highlights/artists/womansartclub Archived April x, 2019, at the Wayback Machine project. Woman's Art Social club of New York exhibition catalog.]

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cecilia_Beaux

0 Response to "People Connect With Family History in Black Cemetery by Matt Allibone"

Post a Comment